Active managers can’t beat their indexes consistently.

Who cares?

During my 25+years of helping people navigate financial waters, I can honestly say I have never had a single client who cared about beating an index – any index – except inflation.

Pretty amazing since most media tend to focus on only two things: Active managers vs. a passive index and cost of ownership. Little, if anything, is ever said about the value provided. To them, apparently, value is ‘nil’.

Actually, our industry is at fault, as well. Look at our quarterly or annual reports. Performance is always measured against an index or some blend of indexes. Industry custodians don’t get it, either.

The ONLY index that REALLY counts is long-term performance measured as progress toward your personal goals, measured in probabilities. Probabilities, after all, are all we really have to work with since there are no guarantees in life. Even our money isn’t guaranteed; it’s “backed by the full faith and credit of….”

So, what approach offers the best chance of meeting your goals? As you might guess, there is no one right answer. The answer will depend on which approach is most appropriate for you.

Managing the downside

When active managers are chosen for a portion of a client’s portfolio, in most cases what the investor is really seeking are returns that outpace inflation while limiting downside risk.

Take a look at this purely hypothetical 10-year market environment. You’ll see our hypothetical market begins and ends with 20-point gains. There are six years of +20% and four years of -20%.

Portfolio A begins with $500,000 and invests in that market. To keep things simple for illustrating this concept, we’ll ignore expenses and taxes. Those aside, you’ll note the average annual compound return and the ending value. The numbers aren’t important except for comparison with the next chart.

IHere’s a hypothetical portfolio that’s been managed for downside risk. Here our fictitious manager is very conservative, capturing only 80% of the upside of each up-market, and also very effective, capturing only 70% of the downside moves. Despite the fact this manager never beat the market on up years, outperforming by limiting losses in down years lead to an overall outperformance.

It’s a made-up scenario, I know, but it does illustrate a concept: Limiting the downside can be quite effective – maybe even more than trying to beat the market indexes and accepting big downside losses.

What if we eliminate the downside altogether?

Insurance companies market their equity-indexed annuities and equity-indexed universal life products with this guarantee. What if you could capture 100% of the upside up to a ‘cap’ of 12%, for example, and be guaranteed that you never lose money? You’ve seen the commercials.

Here’s the same hypothetical market return, this time compared to the strategy that eliminates downside risk! Wow! Looks good! Compare the ending values with our manager limiting losses in the prior example. Now, even if you factor in expenses and inflation, it would still look pretty good.

But, does this method outperform in all markets?

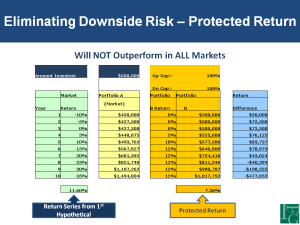

In this third chart, I’ve created another hypothetical series of market returns starting at -10% and moving all the way up to +35% over ten years. There are only two down years, yet despite that, this market return series outperformed the guaranteed return. In fact, our downside guaranteed portfolio came in $477,000 BELOW the ‘market’ portfolio.

You could create a million market return sequences and come up with a million different variations. The point is while these downside guarantees don’t necessarily mean you will make more money, they can provide a valuable ‘protected’ return.

Again, who cares? If the portfolio is advancing you to your goals, that should be all that counts.

But, how do you position these guaranteed products in your portfolio?

What asset-class should they be assigned to? Just because you may have participation with a stock index, do those assets get assigned to the stock portion of your allocation? If not, why not? And, how would you position them?

The answer might surprise you. Many retirement plans may fail. Some time ago I created a report on this subject – you might find it helpful. You can access it here.

Enjoy!

Jim