Should You Believe Insurance Company Illustrations?

Jim Lorenzen, CFP®, AIF®

Just in case you haven’t heard, Genworth has decided to suspend life insurance and annuity sales. This decision will leave many agents and their client with questions on where to turn and how to get protected.

Insurance companies seldom discontinue a business segment when it’s either profitable or if they haven’t overextended themselves. Remember Executive Life?

Before Executive Life of New York went under, they had over 50% of their portfolio invested in less than investment grade ‘junk’ bonds, despite the fact that in June 1987, the New York legislature had mandated that insurance companies licensed to business in that state were to limit their general portfolios to no more than a 20% allocation to such bonds. Remember, there are no guarantees; there are only guarantors. [Source: The New Insurance Investment Advisor, Ben G. Baldwin, McGraw-Hill 2002, p. 37.].

A qualified advisor would/should have looked “under the hood” at the company’s investment asset allocation and quickly realized it wouldn’t be used in a client’s portfolio; so, why would anyone use it to back their retirement or legacy planning? Unfortunately, as all too often happens, insurance companies can take ill-advised risk in order to promote unrealistic return rates to pump-up sales.

Life insurance illustrations have had, for more years than I can count, a well-deserved reputation for less than transparent and amazingly inaccurate projections of what the policyholder could expect in future years. The unfortunate result is that one of the most amazing financial products on earth – and life insurance does far more than most people even suspect – has suffered from a plethora of negative bias, both in and outside the media universe, and virtually all of it wrong.

A regulatory solution?

A recent regulatory change recently took affect that limits the growth rate an insurance company can use in its illustrations to a maximum that’s based on the company’s current ‘cap’ rate applied to an average rate history going back over 50 years. The key is that the company can use its current cap – which actually can function as an incentive to keep the caps high, maybe even unrealistically.

This could mean – and what many unsuspecting consumers may not realize – that it may also act as an incentive to take on additional risk in the company’s underlying general account investment portfolio. Insurance company actuaries are good at manipulating numerous ‘moving parts’ that can make attractive caps look better than they really are. Does a company offering a 13% cap on an indexed product really perform better than one offering only a 10% cap? According to some extensive back-testing I’ve seen, it doesn’t seem to be the case – expenses often play a more important role

One major problem for the typical insurance consumer is the inability to tell one company from another. While many truly professional and credentialed independent agents do make an effort to represent only “investment-grade” companies, there are those who will represent the highest commission, which can often lead to selling substandard products for companies that appear to be substantial. An agent who is also an investment advisor can be a benefit for the buyer.

Most of the well-known rating agencies you may be familiar with are actually paid by the insurance companies they rate! Little wonder many insurance companies that failed actually had good ratings when they went under.

Have you noticed that virtually all insurance companies tout ratings from the same rating agencies in their promotional materials? Few, if any, however, tout their rating from Weiss, maybe because Weiss doesn’t get paid by the companies they rate – their revenues come solely from subscriber revenue (kind of like Consumer Reports).

For example, according to the September 2002 Insurance Forum, of 1221 life and health companies rated by Weiss, only 3.9% of companies made it into the ‘A’ category. Compare that with the 54.9% rated ‘A’ by Standard and Poor’s. At Moody’s, 90% of their list made it to ‘A’ that year. A.M. Best gave ‘A’ to 56.3% of the companies they rated. [Source: The New Insurance Investment Advisor, Ben G. Baldwin, McGraw-Hill 2002, p. 405.].

By the way, Companies with ratings in the A or B brackets from Weiss are considered secure, while some of the other rating agencies will give B and even A bracket ratings to companies considered vulnerable.

Recently, indexed universal life (IUL) policies have become quite popular – both among agents and their clients. The reasons are many, but two big attractions are (1) transparency – virtually no hidden moving parts. These products are easy to understand; and (2) low cost – insurance costs are basically like term policies. Admin costs are also low and, as noted, everything, including costs, is transparent, including performance going forward.

Does that mean the illustrations can be believed? No, but for different reasons. To understand the reasons why illustrations can be misleading and how to know you’re comparing apples with apples, it’s important to know how these policies work.

First a caveat: This is not an exhaustive text on IUL products and there’s a lot more to know than is being discussed here. This is simply a quick overview highlighting the stand-out characteristics.

IULs are often, but not always, designed as financial tools for maximum cash accumulation in a tax-advantaged vehicle. In these cases, the death benefit is often a secondary consideration; however, it’s the life insurance that buys the tax benefits – and, for many, these benefits far outweigh the cost of insurance, which is typically priced like term insurance.

Unlike most insurance buyers who want the most insurance for the least amount of money, these buyers want to buy the minimum amount of insurance for the maximum amount of premium they can put in (yes, there’s a limit). This is because after the minimum insurance is purchased and expenses are covered, the rest goes into a cash accumulation account; and in an IUL, it can be tied to an index with much higher caps than are usually available in an annuity.

The cash accumulation account accumulates tax-deferred, but can be accessed for retirement income later as tax-free loans. How fast does the cash accumulate? Interest is credited to the account based on the performance of an outside index. While there are often many choices, most people tend to choose the S&P 500 index.

To keep this simple, I’ll just quickly cover the simplest approach: Let’s suppose our policyholder purchased an IUL policy using the S&P 500 index as the crediting option. The policy might offer 100% participation in the index’s upside moves up to a ‘cap’ during a crediting period, typically one year. For example, if the index rises 8% by the policy’s 1-year anniversary date, the policyholder participates 100% in that move and receives the full 8%, provided the ‘cap’ is higher. If the index rose by 25% and the policy ‘cap’ was 11%, the policyholder would realize a credit of 11%.

So, on a 1-year, 100% participation with a 11% cap, a 25% rise in the index means the policyholder would receive 11%, i.e., 100% of the increase up to the cap. That amount would be credited on the policy’s anniversary date

The next crediting would take place on the policyholder’s second anniversary. Note: It doesn’t matter what happens between anniversaries – only the value ON the anniversary date counts, nothing else.

The good news is that if the stock market index has a drop, the policy loses nothing. The amount credited is 0. No gain, but no loss, either. Another nice thing is that, in our example above, after the 12% gain is achieved, it’s locked-in. That’s the new floor and that money can’t be lost.

To understand how beneficial a ‘no-loss’ concept is, it’s worth remembering that while a drop from 100 to 80 represents a 20% loss, to get back to 100 from 80 requires a 25% gain (20 points up from 80 is 20/80 = 25%).

How can the insurance company, investing in a conservative bond portfolio do this? It’s simple. Again, I’ll oversimplify with rounded numbers just to make the concept easier. Premium money received by the insurance company might be invested 95% in bonds, and 5% in stock options. If the market goes down, the options expire; if the market goes up, they execute the options and, of course, the cap on the policy limits their exposure. So, the pricing of options, as well as the length, impact costs.

Important: The policyholder is not invested in the market or the options. The index is only a ‘ruler’ to measure how much the insurance company will credit. It’s the insurance company’s investment account that is doing the investing, not the policyholder.

Returns and Illustrations

Can the policyholder really receive stock market-like returns? Not likely. The caps limit the upside, and while there is no downside, down years representing no gain will sometimes occur. So, positioning IULs as a stock substitute is probably not the best strategy. I would look for returns that are more bond-like – maybe a little better – which means, it’s the bond portion of your portfolio that you’re really dealing with.

And, here’s where illustrations can be a bit misleading.

If one company is offering a 12% cap and another company is offering an 11% cap, but both are showing you an illustration using a 7% crediting rate, saying that the S&P average over all their back-tested periods indicates that 7% is conservative, are you really seeing an apples-to-apples comparison?

Now that new regulations limit the cap that can be illustrated – remember, however, it’s based on the ‘current’ cap rates for each company applied to historical data, placing an incentive for the company to keep current rates high – it’s probably better to simply ‘level the playing field’.

First, the company: How have they treated policyholders in the past when they’ve reduced or increased their caps? Did existing policyholders receive the same treatment as new policyholders? Believe it or not, not all insurance companies treat their existing policyholders the way they treat their new ones.

Secondly, a decrease in a cap rate isn’t all bad. Responsible insurers are custodians for client assets and need to act responsibly, rather than chase risky investments to meet caps they can’t pay. However, a decrease in the cap also can affect your outcome.

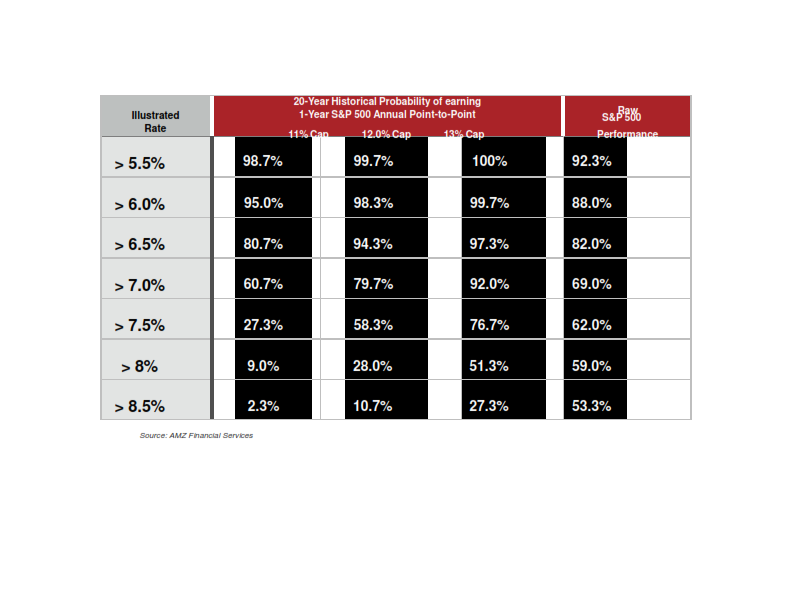

Take a look at the chart below. Noticea 7% illustrated rate for a 12% cap IUL has had a 79.5% chance historically of meeting its projections, based on a 20-year probability study of the S&P 500 at various cap and crediting rates. If the cap is 11%, the probability is reduced to 60.7%.

The new regulations stress average results; but, it provides little comfort to know that your own retirement results have a 50-50 chance of being better or worse.

This has less to do with the insurance company than it does with expectations. It’s important to know, when you’re buying, what you can reasonably expect; and, often, it may not be what you’ve been promised with a rosy illustration. High quality companies providing investment-grade products will tend to be conservative in their projections – and a good advisor will educate clients on realistic outcomes.

Key Point: An illustration for a policy with an 11% cap but using only a 6% crediting rate may not look as rosy as the 7% illustration, but the odds of the company delivering on its promise rises to 95%. This means, it’s virtually certain your policy will perform this well or better. The 7% illustration will look so much better at the point of sale, but it also has almost a 40% probability of doing worse than promised.

So, when comparing companies, wouldn’t it make more sense to have them all illustrated at 6%? By doing so, you could see how they perform on a level playing field with a higher success probability. You can compare high probability outcomes and, more importantly, a basis for comparing costs, as long as the policies being compared have the same features, riders, etc.

The Real Benefits

If someone begins utilizing these benefits early, say in their 40s or 50s, the retirement benefits can be substantial. As a matter of fact, it’s a retirement strategy being used by 85% of Fortune 500 CEOs and many members of Congress in order to create a tax-free retirement. Other proponents of this strategy include retirement and IRA expert Ed Slott, who is also a CPA, and David M. Walker, former US Comptroller General [Source: The Power of Zero, David McKnight].

I’ve created a report on this concept. You might find it interesting. You’ll receive it free by going here. If you’d rather take the time (about an hour) and view the webinar with all the slides, you can do that here.

Enjoy!.

Jim