The financial landscape is known for its complexity; and the plethora of confusing financial products – not to mention the alphabet soup of designations and certifications – can present a daunting task for any normal person to unravel. And, every time the market changes, the product vendors come out with another solution.

The financial landscape is known for its complexity; and the plethora of confusing financial products – not to mention the alphabet soup of designations and certifications – can present a daunting task for any normal person to unravel. And, every time the market changes, the product vendors come out with another solution.

When you add to all this the media gurus who want you to buy their DVD packages instead of ‘throwing away’ a penny per dollar for professional advice – and who can blame anyone for listening when anyone with a license to sell can legally call themselves a ‘financial planner’ – it’s a situation that would make most sane people want to throw up their hands and run to live in the forest.

Of course, consumers do have their share of responsibility for taking the easy route – relying on television gurus and consumer magazines trying to sell circulation – rather than actually laying out money for more academically-oriented educational material or investing in qualified advice.

So, at the risk of appearing as simplistic as the media gurus, I thought I’d just provide some simple mathematical insights. I hope you might find this somewhat helpful.

Buying back losses is difficult.

It takes about a 43% return to buy-back a 30% loss. If an investment suffers a 30% loss, dropping from 100 to 70 for example, it would take a 42.9% return just to get back to even (30/70 = 0.4286).

Realizing that, limiting downside exposure can be quite helpful. For example, take a look at this hypothetical scenario below. Portfolio A is invested in our hypothetical market and Portfolio B is managed for limiting downside risk (also purely hypothetical). While our fictitious manager captured only 80% of the upside (never beating the market), s/he was still able to ‘beatthe market’ long term by limiting downside capture to only 70%.

It’s all hypothetical theory, of course, but it does demonstrate a principle: Limiting downside loss can be more powerful than upside capture, particularly since most managers do not outperform the market and virtually none consistently outperform the market long term.

Television gurus make a big deal out the fact managers can’t beat indexes, but it’s a false argument. An index is not a measure of what YOU need to do. Your GOALS are what’s important, and whether you’re on track.

Indexes do not have expenses and they also don’t pay taxes. If your house went up in value perfectly tracking an index, would you have tied the index? Of course not. An index doesn’t have annual expenses like interest expense on your mortgage, maintenance, repairs, insurance, and property taxes. If you add those expenses and then compute the return you’d need to ‘tie’ the market, you might be astounded – that’s bigger than `surprised’, but I digress.

What if you could eliminate the downside?

Let’s suppose you could, hypothetically, never lose money with a trade-off than you would have a limit on how much you could achieve as a return each year? What would that look like?

Let’s suppose you would never lose – if the market lost 5%, your return would be 0%, i.e., no loss, and in exchange you could never make more than 10%. How would you fare?

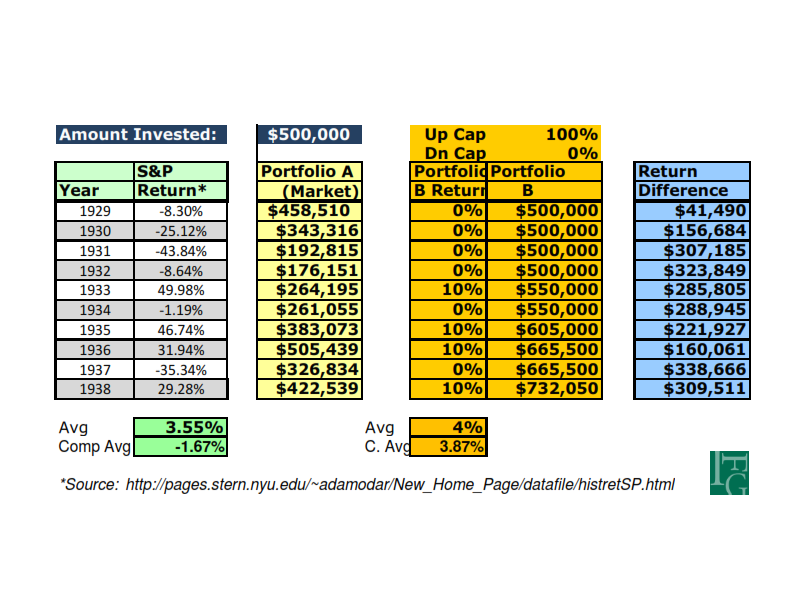

Let’s start by taking a look at what was probably the worst ten-year period in history: The period from 1929-1938 – the crash and Great Depression.

Portfolio A, if it had remained invested throughout the entire period, would have seen a $500,000 portfolio reduced to $422,539.[i] As you can see, our hypothetical ‘no-loss’ but capped at 10% portfolios would have grown to $732,050. But, what’s interesting are the percentages!

Many companies love to use ‘average’ (arithmetic) returns, which simply add-up all the annual returns and divide by the number of periods, in this case, 10. Looking at a simple average, we can see the difference is only 0.45%. But, this isn’t the return percentage you want to see.

The average annual compounded (geometric) returns are more telling. Those returns tell you what actually happened to the investor! As you can see, the compounded return for the period was -1.67% per year for the ‘market’ investor, and 3.87% for our hypothetical Portfolio B – a spread of 5.54%!

A little more food for thought

All your life you’ve been told to ‘max-out’ your 401(k). Should you?

Well, up to your employer’s match, it can make some sense; but,, how about unmatched money?

Suppose you invest $5,000 a year for 30 years (total of $150,000) and average a 6.5% return. Your total at the end would be about $463,000, depending on timing of your deposits. But, while your statement may show $463,000, much of it will belong to Uncle Sam.

How much? It depends on what the tax laws are during your retirement. If you withdraw $50,000 each year of retirement and are in a 30% tax-bracket, you’ll pay $15,000 in taxes each year. In ten years, you will have paid $150,000 in taxes; but, the chances of your retirement lasting 20 years or longer is probably very good, which means $300,000+ in taxes. And, if you’re like many who live three decades in retirement, you could be facing more than $450,000 in taxes!

How much? It depends on what the tax laws are during your retirement. If you withdraw $50,000 each year of retirement and are in a 30% tax-bracket, you’ll pay $15,000 in taxes each year. In ten years, you will have paid $150,000 in taxes; but, the chances of your retirement lasting 20 years or longer is probably very good, which means $300,000+ in taxes. And, if you’re like many who live three decades in retirement, you could be facing more than $450,000 in taxes!

But, wait! Your 401(k) had only $463,000 to begin with! Welcome to longevity risk… and that’s if the tax laws don’t change – good luck.

Another option: Instead of paying taxes on “the harvest” as we did above, you pay taxes on “the seed”. We’ll use the same example: $150,000 invested over 30 years earning 6.5%. If you pay taxes on the money as you earn it over 30 years, your total taxes paid by the end, using the same 30% tax bracket, now come to only $45,000! Big difference, ya’ think?

Your $3,500 annual investment (after taxes) would, depending on the timing of your deposits, would probably grow to around $322,000 – again using the same 6.5% average annual return.

Whether or not you pay any capital gains on realized gains, during the period or at withdrawal, will depend on

(a) the tax laws at the time, and, more importantly,

(b) how the money is arranged and held until retirement.

There are people who do pursue a tax-free retirement strategy. If you’re interested, you can learn more about that in a one-hour on-demand webinar I’ve recorded, which you can access here. I think you’ll find it eye-opening, if not helpful.

James Lorenzen, CFP®, AIF®

[i] This does not include any expenses or taxes (indexes don’t pay either) and you cannot buy an index anyway. You can only purchase shares of an index mutual fund or an exchange –traded fund (ETF).